FIRST SOLO FINISHER IN 2019 RACE TO ALASKA

31st August 2019

Freedom Marine team member Shawn Dunand talks about his experience becoming 2019’s first solo finisher in the infamous human- and wind-powered Race to Alaska!

Grit. It’s a tool in every sailor’s arsenal, usually kept within reach of patience and discipline. Earlier this season Freedom Marine team member Shawn Dunand trotted out all three of these attributes, along with a boatload of veteran-level knowhow to become 2019’s first solo finisher in the notorious 750-mile adventure race from Port Townsend, Washington, to Ketchikan, Alaska, known as R2AK, the Race to Alaska.

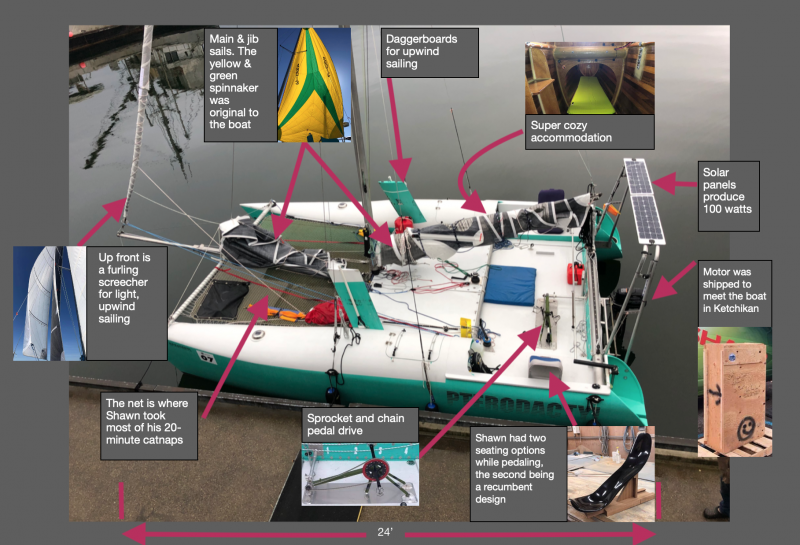

The rules for this human- and wind-powered race, North America’s longest, are simple. Any boat can enter as long as it doesn’t have a motor, or a support crew. Sounds a bit crazy, right? And it was, because on the same roster as the fully-prepped race boats with crews of six or seven, there was a guy from the Netherlands on a SUP and a couple from Maine in a row boat. Dunand was somewhere in the middle of the range, piloting a 24’ performance catamaran, built from derelict parts he’d rescued from field storage on Salt Spring Island.

This photo from R2AK’s Facebook page is a great example of the disparity between the fastest and slowest human- and wind-powered vessels in the race.

The organizers behind R2AK are upfront that this adventure race isn’t an event for everyone, likening it to the Iditarod, only on a boat. And like the Iditarod, it’s as likely to bring you to your knees as it is to bring you glory at the finish line.

THE PROVING GROUND

So how do you qualify for such an arduous event? “Convince us you’re not going to die,” instructs the R2AK website. Although there are no absolute qualifications, resumes are considered, especially for “teams of one,” like Shawn on his catamaran. You need to tick the boxes on a virtual checklist of skills such as navigation, radio use, voyage logistics and on-the-fly repair skills. As for your vessel, it needs only demonstrate “inherent buoyancy” during a cursory inspection.

There are, however, two stages during the Race to Alaska and with good reason. Stage One, a.k.a. The Proving Ground is a 40-mile sprint from Port Townsend, Washington, to Victoria, BC, much of it open water as it crosses the Strait of Juan de Fuca’s two sets of shipping lanes plus an international border. As you can imagine, this is where the wheat is sorted from the chaff.

Alex de Saint on his Airboard SUP. He’ll be back in 2020.

“The water conditions for that run could be anything from lake conditions to what we had,” says Shawn of this year’s 5 a.m. start, which was preceded by overnight winds of 35-40 knots and a promise for more. Gale for wind combined with the significant ebb tide to create some really steep, nasty waves that beat up many boats, and simply overwhelmed many of the human powered entries. In fact, the kayaks and SUPs had to beach their crafts and wait for a break in the wind before they could carry on. In the end only 36 of the 50 craft that left Port Townsend arrived in Victoria within the 30-hour time allotment.

Shawn took 13th place in this difficult first phase, limping into downtown Harbour with a split hull 6 hours after the start, and put his hopes for the full race in question. It would take a miracle to make solid repairs while the boat was in the water during the layover, and as he set about scrambling for a way to make it happen, he quietly questioned his sanity. It wasn’t the first time.

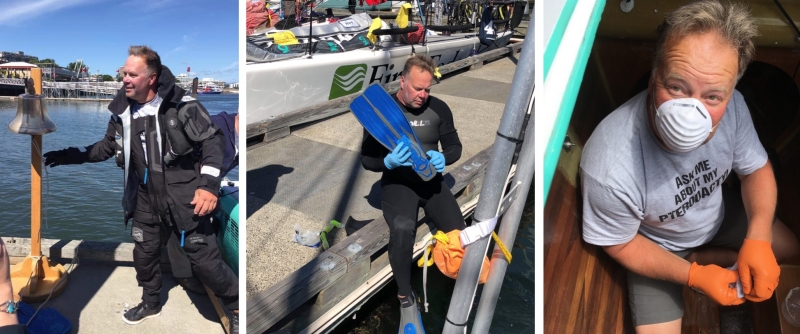

Moments after Shawn rang the bell in Victoria after a brutal Stage 1, he went to work trying to repair damages to Pterodactyl’s hull.

SEEDS PLANTED, BOAT PARTS HARVESTED

The R2AK started off with a bang in 2015, the brainchild of Jake Beattie, the executive director of the Northwest Maritime Center, who told reporters at the time he envisioned it as “a kind of inquiry into human ingenuity.” He wanted to see what people could come up with. Since then, it’s been a celebration of inventions and daredevils and the testing of wills.

Shawn Dunand, who works full time out of Freedom’s Sidney location is a sailor to the core, being put to sea on countless solo trips. His friends would tell you he’s enterprising, detail-oriented and skilled with his hands, so as you can imagine, the R2AK struck a cord the moment a friend introduced him to it. But being more reasonable than he is nuts, it took a couple years of following the race before he decided to jump into the fray.

First things first, he needed to find the right boat. “Instead of buying a real boat I decided to buy a project boat,” he muses, recalling the year-and-a-half it took him to rebuild “Pterodactyl” a homebuilt cat that had pieces stored and tucked across Salt Spring Island for 15 years. The first questions about sanity came during the year-and-a-half he spent trying to turn the pieces into a functioning boat: “Imagine spending all your social capital – time with your partner, your friends and time you could be making money alone in a shop doing fiberglass work,” he laughs.

Pterodactyl when Shawn brought her home.

Pterodactyl ready to fly!

STAGE 2 A.K.A. “TO THE BITTER END”

So while Shawn busied around Victoria Harbour desperate to perform just a little more fiberglass work, his partner Leah was right there to support him. “My family was in town too and I hardly got to see them,” says Shawn. “they were running around getting the supplies and groceries I was supposed to have time to get, but I was in full-time boat repair mode the whole time.”

Shawn’s shore crew in Victoria included dad Harvey, mom Shirley (not shown) and his partner Leah Hutchings who he credits with being incredibly patient during the two years it’s taken to get Pterodactyl race-ready. “She thought I was nuts when I brought the boat home in pieces.”

Thanks to a last-minute loan of some airbags, and assistance from fellow boaters, Shawn was able to lift the hull and repair the damage from the inside, finishing just before the kickoff of Stage 2.

During the layover in Victoria, Shawn is loaned some airbags in the 11th hour allowing him to repair the cracked hull just in time to carry on.

You’d think it would be a satisfying moment – perhaps even peaceful, to just sail after so much effort getting yourself and the boat ready, but Shawn will tell you the real work had only just begun. While he had some good wind right out of the gate, by the third day he and five or six other teams hit a calm. “We had pretty much no wind for two days,” he says. “But that doesn’t mean you’re resting; you’re pedaling or rowing constantly.”

In addition to the monumental physical challenge, racers need to deal with extreme cold and constant sleep deprivation, though far less among teams with a larger crew who can trade off turns on the tillers. Shawn says racing the event solo had all the problems of normal solo sailing, “You need more hands and you’d love to trim or do something to make the boat more efficient or more comfortable but you’re already doing everything you can.”

From a distance Pterodactyl looks serene, but onboard Shawn is pedaling his heart out.

The ten days it took Shawn to get from Victoria to Ketchikan proved to be the biggest challenge he’s ever faced, and while he never thought of quitting, he did come upon some real hurdles, including a few bouts with hypothermia and a close call or two, like the time he was sailing in pitch dark and strong current swept him along a rock and cliff shore. “The GPS was actually showing me on land,” he says. “I could see the outline of trees overhead, but I had no wind to fill the sails. The only thing that saved me was finding a line to angle against the current and pedaling as hard as I could.

HIGHS AND LOWS

There were incredible moments too, like the night he was leaving Johnstone Strait. There wasn’t a breath of wind, but he’d caught a current so peddling was finally getting him somewhere. “It was the middle of the night,” he says, “and I could really notice the smell of the water changing as warm water mixed with cold.” A bright phosphorescence began lighting up the boat, and then came the sounds of wildlife. “Whales were smacking their fins right next to me and the sound was echoing across the water. Sea lions were barking too.” He says for about three hours he was just soaking it all in.

No shortage of beautiful sunsets, this one looking at Aristazabal Island.

No shortage of beautiful sunsets, this one looking at Aristazabal Island.

Sleep deprivation was by far the hardest challenge of Shawn’s solo sail. In 10 days underway he only allowed himself to anchor and sleep three times, once for 2 hours, once for 4-5 hours and once for 10 hours. The rest of the time he was trying to grab 20 minutes when he could but explains that your mind and body are still listening so you’re not getting true sleep. “You’re right there on the net so you’ll feel a wind change and need to get up and make adjustments.”

“There were periods I had trouble standing,” he says. “I’d get rubber legs.” Shawn also encountered some of the mental glitches associated with prolonged sleep deprivation, such as auditory hallucinations. “Things like the mast creaking would sound like music after awhile, or the wind would sound like voices saying things over and over again.”

Fashion doesn’t matter when you’re freezing!

To combat the hypothermia inevitable when you’re sailing an open, flush deck catamaran in high seas and pouring rain, Shawn huddled around his tiny Jetboil camp stove. “I’d be soaked the bone,” he says. “Water would be rushing over the boat and running through my jacket and up my pants legs. The stove was a lifesaver, along with a hot water bottle I could drop in my bibs.”

BRINGING IT HOME

After getting calmed for several days in the beginning of the race, Shawn found a strong southerly in Hecate Strait and with the cat surfing well, he ended up blasting out the last half of the course in just three days (it had taken seven pedal-heavy days to get halfway).

Every sailor knows you get what nature gives regarding wind and weather, and some of the top players had higher constant speed that rewarded them with more consistent winds after passing through Queen Charlotte Strait just ahead of the calm that slowed Shawn. This, evidenced by the realtime tracking records as well as the finishing times, which show 10 boats arriving on days 4 and 5, then the next boat crossing the finish line on day 7, almost 48 hours later.

Shawn finished strong on day 10 ringing the brass bell in Ketchikan with a huge, half-delirious smile on his face. While he’d never intended to win the $10,000 first place purse, or even the set of steak knives jokily awarded for second place, he had hoped to break the record of 8 days for a solo crew. Which, of course, opens the door for another go next year.

Shawn’s arrival at the finish in Ketchikan, Alaska.

“During and just after the race I said no way, I will never do this again, but as the months go by you forget about the hardship and start thinking, well, maybe if the situation was right….” After three days resting up in Ketchikan he began an 11-day solo journey home, this time with a motor and time to sleep.

On the way back down the coast he passed the couple from Maine in their rowboat, both in good spirits and still on track to finish in Ketchikan. The Norwegian SUP guy had been outdone by high seas but vowed he would return to conquer the R2AK next year.

Dameon Colbry and Leigh Dorsey were still rowing their way to Alaska as Shawn was headed home. They finally arrived on Day 17.

Crazy as it seems, what draws people to race their self-powered rigs to Alaska is undoubtedly the same list of things that bring us to sailing in the first place: The challenge of harnessing one of the most powerful forces in nature as a means for personal exploration, combined with the deeply satisfying power that comes with self-efficiency. And maybe more than anything, it’s having enough grace to invite the sensation of feeling tiny. Of being humbled.

Heading home, Grenville Channel looking North

If you’re not up for making your own bid in the 2020 R2AK, be sure to follow it next June on the official website where GPS tracking allows armchair fans to watch each teams’ progress in real time. Daily podcasts fill you in on all the details.

Meanwhile, the next time you see Shawn on the docks give that guy a pat on the back!

On the trip home Shawn relished simple comforts, like being able to dock for a good night’s sleep.

Spectators.

Two contrasting modes of sea travel. Shawn’s pedaling rig in the foreground was the only means for making time during two full days without wind.

Mustang Safety, one of R2AK’s 2019 sponsors, followed the race in an Axopar 28 owned by Freedom Marine customer Wayne Gorrie.

Pterodactyl details.